|

| "The Franklin's Tale". image courtesy izquotes.com |

Neither "mastery" nor its variant forms featured significantly in my own career, in which academic context, I'd say only "master" was in general circulation: it meant "male teacher" and a higher degree.With regard to learning, my students "learned", "got", "grasped", "understood" and "appreciated". Pennies dropped. I neither set out consciously to develop "mastery" nor indicated that state may have been achieved. None of my colleagues were officially designated "master teacher", "expert", "highly-skilled leader" "outstanding" or "guru". They were simply "head teacher" or an "assistant teacher" with or without additional paid responsibilities.

In retirement, I follow as best I can what's happening in schools and have observed a sea-change from shared appreciation of the implicit to a systemic impulse for explicitness. So universal is this shift that it re-contours every hill and valley of education's landscape. The forces driving this change are I think generally understood, embraced and opposed with equal passion. The impact on the classroom is for me the litmus test and in a future post I'll look specifically at the virtue of leaving certain matters implicit in lessons. Here I just want to sound a note of caution on the deployment of "mastery" in the terminology of learning and argue against the concept of "Master Teacher" as a promotional post in schools.

"Mastery".

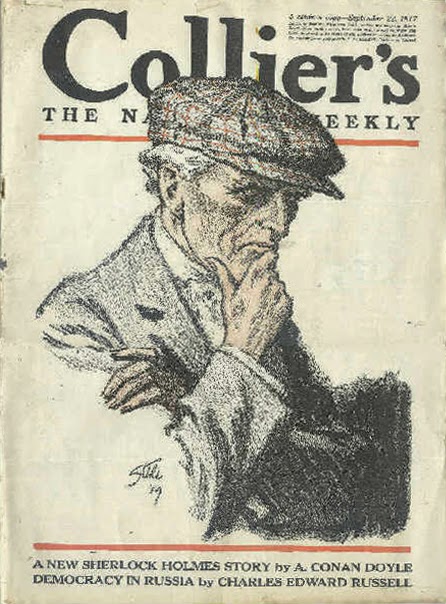

There is the world of difference in the general use of a word and its formal adoption to make explicit reference to a state of educational achievement. I can speak with equanimity about Carl Faberge's mastery, indicate Professor Moriarty's genius as a criminal "mastermind" or recommend John Barton's "Playing Shakespeare" series as a "masterclass" without the need to delineate every "masterly" feature. If, however, a choice is made to deploy the word in the context of learning, descriptive criteria and a case for its value are essential.

There is, first of all, in my own subject, a well-populated set of topics just not amenable to "mastery". I've been (enjoyably) in near constant company with rhythm and metaphor for some 55 years: it would be presumptuous and meaningless to claim mastery of either. Certainly one may come to identify, describe and comment critically on the use of sprung rhythm in the poetry of Hopkins. Similarly, the distinction of metaphor from simile, their effective use in a student's own writing & their appreciation do educate. However, despite decades of responding to imagery, so elusive is this literary technique in its density, manifold layering and resonances that I'd never claim "comprehensive knowledge or skill", still less "control or superiority" - the (related) strands of mastery's definition. I have noted elsewhere that ( along with appreciation of form and of narrative voice) the imaginative act of experiencing images is one of the most common and difficult matters to nurture in A level students.

Secondary English teachers will be aware how commonly one revisits of necessity even the awareness of alliteration. Not that it hasn't been explicitly taught in earlier years. Much the same applies to words commonly confused.

Now, such knowledge would initially seem more open to teacher and pupil recording "mastered" after being taught, practised and tested. My own education is characterised by just this process. While not exactly in possession of a photographic memory, I revised for O and A level exams by hypnotising myself and looking at my exercise books so often in that state I could see the pages in my mind in the exam room. I got the lowest pass grade in Maths by writing out geometry theorems suggested by questions I didn't understand.

As with all the play scripts I've learned over the years in amateur theatre, almost every detail absorbed for every exam I've ever taken was forgotten within a fortnight. My mind evidently says what is retained is that which is of current use. Keep testing me, I'll retain it.

The underlying question here is "Just when does mastery come?" Logically, one would need to test the adult decades after leaving school to rubber stamp "Mastery." You have to keep on making Faberge Easter Eggs (and die, ironically) to earn that accolade.

So the problem I have with this word in the context of the classroom is its too slick, premature implication of accomplished in both senses of the word. This is self-defeating - the very act of claiming mastered! limits progress and I think, in over-egging achievement does the pupil no favour and demeans a word descriptive of a rare phenomenon, best kept for Old Masters.

The more explicit and measurable you make the stuff of a lesson, the shallower the experience becomes. And, in truth, I have to conclude that the impetus for mastery derives more from its signification of control - which leads right back to that systemic anxiety to appear to be in control, to want control. At root, therefore, I think the illusion of mastery serves the exercise of power, not children. For me, the only virtuous manifestation of control in the classroom is in the maintenance of humane, consistent discipline.

Master Teacher.

Whichever party is in government after the next election, there will be temptation to dust off existing, common proposals to create posts for Master Teachers (or a less gendered, less American title) as a perceived, logical fine tuning of Performance Related Pay. The Coalition's original (shelved) proposal of 12/12/2011 may be viewed HERE .

Were I still in service, I should decline such a position were it offered and view with dismay the appearance of such beings on my staff. As with mastery there is a realm of difference between complimenting a teacher as great, outstanding, inspirational, highly-skilled, fabulous, cool or a legend! and employing and paying you formally for being thus. As far as I am concerned, an employment contract entails a job to do and someone to do it. A job which breaks down into jobs, not personal qualities. It matters not who constitutes any "independent board" to draw up final criteria - the commitment to a monumental mistake would have been made already.

I wonder:

For how long would a Master Teacher be appointed? Such characteristics as those in the proposal would surely necessitate constant demonstration to justify continuance.

What impact would this have on teachers? The collation of supporting evidence by one ambitious for such a post would be onerous and significantly modify behaviour with staff and students. Some teachers would be advantaged in appearing suitable by a lighter work load or membership of a high-profile department.

How close to the realities of a school are the elements in such a proposal? DO such creatures exist who, term in term out, display unerringly such qualities? Not in my experience.

Is it not simply shallow to imagine only certain members of staff are beacons of advice? The Teach First group in Channel 4's series sought out each other. The staff room is a community with freedom to approach those we trust, respect, like or sense as kin. A charismatic figure may be the last thing you need in your confidence.

The introduction of such a structure would formalise what should be natural and distort relationships. You should pay teachers for what they do not what they are - or more precisely what they have to wrench themselves into being to conform to an ideal model that demeans anyone who tries to personify qualities rendered explicit which were best left implicit.

Go into any staff room and everyone knows who shines that little bit brighter. Occasionally you have the honour of serving alongside a great soul. They require no payment, not even recognition. We do not envy them: we are grateful. We never tell them of this, directly.

You can keep your Master Teachers: the greatest compliment I ever was paid (and it moves me now to recall) came heavily disguised in the graceful guise of implicit love when the school secretaries dubbed me "the ordinary teacher".

© Ray Wilcockson (2014) All rights Reserved